Views: 35

Lead Engineer William Wu | Innovative Engineering Solutions

William Wu is a technologist and CEO of QED, a company that builds digital data systems and machine learning solutions for agriculture and health.

NEW YORK — The African Soil Information Service — a global initiative to build digital soil maps for Africa that now falls under a new program called Innovation Solutions for Decision Agriculture — was having trouble converting one file format to another.

“There seems to be a shortage of people like us working in aid.”

— William Wu, engineer, researcher, and CEO at QED

“It could be done with four lines of code,” said William Wu, CEO of QED, or Quantitative Engineering Design, which builds data systems and machine learning solutions for agriculture and health projects. “They were stuck on something that I could do in 30 seconds that was blocking them for months.”

When Wu offered his help in 2012, the organization had no software engineers on staff, and within three years, QED was working with AfSIS, now ISDA, on digital infrastructure. A lack of expertise in computer software and hardware is consistent across many aid organizations, whether it is because they do not see how these skills would be useful, or they have a hard time hiring professionals who might otherwise work for technology companies. William Wu spoke with Devex about why he started QED, what solutions he and his team are working on, and how to engage more engineers in international development.

“There seems to be a shortage of people like us working in aid,” Wu said.

Most software engineers seek out jobs at top technology companies, including Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google, he explained.

“On the other hand, you’ve got all these other projects trying to pursue problems that are more meaningful, and there are almost no engineers on these projects,” he said.

While tech companies can offer higher salaries, engineers in Silicon Valley and beyond are often cogs in a machine, Wu explained, whereas part of the appeal for technologists working in international development is that they are indispensable.

“Today, I’m going to talk to you guys about dirt,” Wu said onstage at the Goalkeepers event organized by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation during Global Goals Week in New York City in September.

As a child, Wu dreamt of being an astronaut. He studied subjects such as physics and computing, and even went on to work at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“My thinking then was the earth is such a tiny spot on the cosmic scale, why do we bother studying anything down here when there’s so much more to see up there?” Wu said.

Over time, he realized that looking further away is not necessarily as interesting as looking closer, he said, explaining that soil is one of the greatest mysteries of the universe, and one of a number of projects QED has taken on that are matters of life and death.

“At this very moment, beneath your feet, there’s a nasty orchestra of earthworms, insects, snails, bacteria, fungi furiously working … decomposing all the dead stuff into the nutrients and minerals that can be accessible to the next generation,” he said. “Therefore, one could say that soil is the resurrecting force that transforms death into life.”

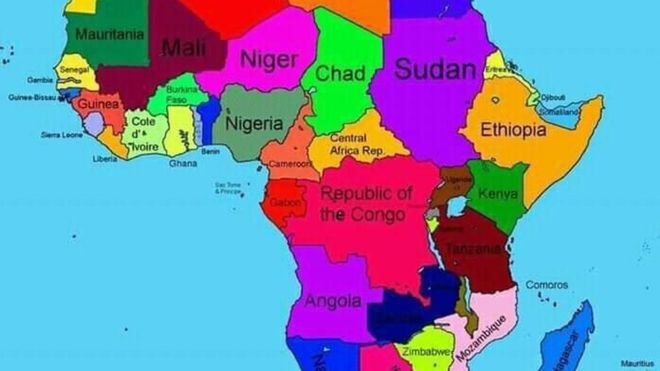

To measure the soil, Wu, QED, and AfSIS had to zoom out from the ground level to space. They crowdsourced an analysis of satellite imagery, then used that data to train a computer, which informed plans for where to collect soil. The soil is analyzed to provide information on what kind of fertilizer to add. But that is only in the beginning of the story, as more information is needed to determine how to support the plant throughout its life cycle.

Get development’s most important headlines in your inbox every day.

QED is a play on the Latin phrase “quod erat demonstrandum,” or “that which was to be demonstrated,” which is the state the team aims for in its work to bring “the hacker spirit to international development.”

When Wu was pursuing his doctorate at Stanford University, he met Jiehua Chen, who was working on her doctorate in statistics and was passionate about international development.

“She needed software engineers and I needed meaningful problems,” he said in a follow-up interview with Devex.

Chen and Wu, who are now married, co-founded QED in 2008, and one of their major focus is global health, including building data systems for hospitals for projects funded by the Gates Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development.

QED is one of a number of organizations working on solving engineering problems in global health and international development. Bill Gates, the billionaire co-chair of the Gates Foundation, supports an invention lab in Seattle, Washington, called Global Good at Intellectual Ventures, and some universities are also taking on this work, often under the umbrella of ICT4D. But what makes QED different is the way it embeds within these organizations and develops solutions together with them.

“In aid, there are a lot of management consultant types, and the deliverable for a lot of these projects is a slide deck,” Wu said. “We wanted to have a different type of company where our deliverable is technology.”

He acknowledged that he faces a number of challenges, with many global development organizations failing to see technology as foundational to their work, or having a hard time describing their needs when it comes to data systems and machine learning. Also, processes such as frequent contract renewals can make private sector engagement difficult.

“Often, we’re still thought of as the help,” Wu added of the perception of engineers across much of the international development industry. “‘Oh, you’re working on tech — my printer is busted. Can you help link it to my computer?”

In his talk at Goalkeepers, William Wu explained that while soil may just be a 1- meter thin layer of the earth’s crust, it is one of the most valuable resources of any nation, and all living things depend on soil to survive.

“If we want to build really high-accuracy maps of soil and plant health, we’re going to need a lot, lot, lot, lot, lot more data,” he said. “And that’s going to require serious moonshot innovation.”

He closed with a call to action for technologists, holding a low-cost, handheld sensor, and asking more people to develop cheaper ways of collecting data at scale.

About the author:

Catherine Cheney

Catherine Cheney is a Senior Reporter for Devex. She covers the West Coast of the U.S., focusing on the role of technology, innovation, and philanthropy in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. And she frequently represents Devex as a speaker and moderator. Before joining Devex, Catherine earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Yale University, worked as a web producer for POLITICO and reporter for World Politics Review, and helped to launch NationSwell. Catherine has reported domestically and internationally for outlets including The Atlantic and the Washington Post. Catherine also works for the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit that trains and connects reporters to cover responses to problems.

Source: YouTube.

You must be logged in to post a comment.